Unsmiling Joe: Life Before NHS Dentistry

Army dentists werre much in demand

imperial War Museum

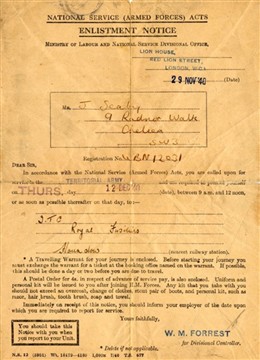

pte joe Seaby's call up papers from the Royal Fusiliers December 1940

Lucy Robjohns

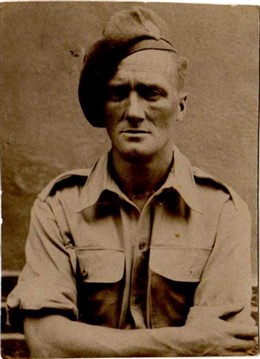

Unsmiling Joe Seaby had all of his teeth removed by the army in 1940

P Daniel

By Gary Faulkner

In December 1940 Joe Seaby received his call up papers and asked to report to Hounslow barracks to join the Royal Fusiliers. Once thing I noticed in all of the pictures that we digitised was that he was never smiling. he ended his letters, "Cheerio and keep smiling," but never seemed to follow his own advice. I spoke with his granddaughter Lucy Robjohns and she explained why this was so. Joe had no teeth. He grew up in so much poverty that when he joined the army at the age of 29, he'd never seen a dentist's chair. Apparently the army often played safe before sending a soldier with rotten teeth abroad by removing the lot.. this was poor Joe's fate. joe was issued with a set of army dentures and lost the bottom set in Italy. he made do with his army top set until he died in 1994.

By the time of the launch of the NHS in 1948, Joe had been out of the army for two years. As an ex soldier he would have been first in the queue for treatment. The new NHS meant, for the first time-ever, that dental care was free at the point of use, but it came eight years too late for poor Joe whose once appointment at the army dentist left him toothless.

The NHS dramatically changed people's appreciation of looking after their teeth. The poor state of British teeth had been highlighted well before Joe Seaby's time. People had been aware of the dentistry crisis since the end of the Boer War in 1902: By then, from 208,300 recruits, there were 6,942 hospital admissions owing to dental causes, of which one third had to be sent home unfit to serve.

In 1948 the nation's dental health was in a worse state than that of defeated and occupied Germany: decay, pyorrhoea, and sepsis were rife. Joe Seaby was not alone. More than three quarters of the population over the age of 18 had complete dentures.

Dentists at the time had concerns about how the new NHS system for dental practitioners would work, and more importantly, how the funding could be sustainable.

An item of service payment system for general dental practitioners was proposed, but the complexities of how this could work and the need for prior approvals and a likely growing mountain of bureaucracy, were felt to have not been thought through. Members of the BDA were polarised as to whether it was a practical option to join the NHS or not.

When the NHS opened for business on 5 July 1948, we estimate that just over a quarter of practising dentists had signed up to work in the NHS.

Dentistry in demand

The demand for dental care on the new NHS was overwhelming. Dentists went from seeing around 15 to 20 patients a day to over 100. Patients had to be turned away, and hospitals also experienced a rise in cases.

The initial hope had been that there would be less emphasis on prosthetics for older people and more conservative treatment for children. However, the demand for dentures was incredible.

In the first nine months of its existence NHS dentists provided over 33 million artificial teeth, a figure that would rise to 65.5 million for the year 1950-1951.

Extractions still formed a large part of dentists' work – 4.5 million in the first nine months – but so did fillings – 4.2 million in the same period.

With the rise in work, dentists' incomes also rose, and the NHS became a more attractive proposition. By November 1948, official figures claimed that 83 per cent of practising dentists had signed up.

More people were being treated than ever before, which had been a main objective of the new service, but this success came at a huge financial cost.

Dentists' fears about the sustainability of the service were justified. Within two years of launching the NHS, the government cut the rates of item of service payments three times, and did so without consulting dentists.

By 1951, the NHS was already running out of money. To help alleviate this, charges for dentures, the first charges of any kind for NHS treatment, were introduced causing much debate in government and the public arena and leading to the resignation of Aneurin Bevan, the Minister who had been crucial to bringing the NHS into existence.

Other charges for treatment soon followed, and unsurprisingly, demand for services dropped.